I am currently in Tucson at the Arizona Methods Workshops refreshing and updating my knowledge on experiments in social sciences. It’s been a number of years since I last conducted a field experiment of hiring, often called an audit study. This research method is deceptively simple—send applications for fictitious job seekers in response to real advertised positions. A researcher pairs two (or more) equivalent resumes or applicants that differ only in the characteristic of interest to the study (that characteristic is called the treatment.) In my research, the treatment is whether or not an applicant served in the military. The matched pairs of resumes are both sent to the same employers, and we observe whether employers respond to them differently or not through the frequency of a callback for an interview.

Field Experiments in Social Science

Experimental research designs are increasingly used in social sciences to estimate the extent of differential treatment, or discrimination because they allow the researcher to control every piece of information that is presented to an evaluator. In this way, we create the ideal world in which two applicants should be treated the same if all the information presented is equivalent. By isolating differences, we can study how that characteristic alone influences how employers respond. For some studies, the key experimental “treatment” is race. These racial discrimination studies have tested hiring and housing outcomes, and use a variety of means to convey race, either through racially distinctive names if applications are done on paper only, or in person with testers of different races. Other examples of treatment of interest are parental status, selectivity of what college one attended, sexual orientation, gender, and more.

By matching everything on the resume but the treatment of interest, the test of differential response is the measured difference in the average response to the applications (although there certainly are more complex analyses one can do as well.) If one group is called back on average 25% of the time, and the other 10% of the time, all that is needed is a statistical test to determine if that difference of 15 percentage points is statistically significant (which would depend on the number of applications sent out.) There are more sophisticated statistical analyses that account for other factors, but the principle is basically the same—statistically compare rates of response to the applications between the treatment and control groups.

This experimental method is especially informative for questions about how veterans are treated in hiring. For now, it seems the veteran unemployment “crisis” has resolved and veteran unemployment is largely comparable to or better than civilian unemployment. But in 2005-2008 and beyond, when it was rising and diverging from civilian unemployment, I heard many anecdotal veteran accounts suggesting they were being unfairly discriminated against in hiring. These personal accounts shared common themes: employers were ignorant about what military service entailed, they saw every veteran as a “baby killer” or a “ticking time bomb”, they feared attention to PTSD cast a shadow of concern over all veterans, or they believed civilians were against the wars and by extension those who served. These explanations always felt off to me—as a sociologist who examined the data, the evidence suggested that the most recent veterans often do not have a college degree coming out of the military, were relatively young with limited direct civilian work experience, and by civilian standards they had generous unemployment compensation allowing them to draw out job searches for a longer period of time. For many, their skills may not directly transfer to the civilian labor market, and veterans had limited understanding of how to translate their skills to civilians. All of these realities painted a different portrait of why veteran unemployment might differ from civilians, namely, that veterans differed form civilians in hiring-relevant characteristics. These skills gaps may result in higher unemployment, but it’s tough to call that discrimination, or even unfair, because veterans and civilians applying to the same job may not in fact be equivalent in terms of their work experience. This is “unfair” only if one believes veterans deserve to be evaluated differently than everyone else when competing for jobs. And, given the existing veteran preferences in public sector hiring, veterans were already getting preferential treatment in one sector of the economy.

Veteran Resume Study: Kleykamp 2009 and Kleykamp 2010 (and unpublished results)

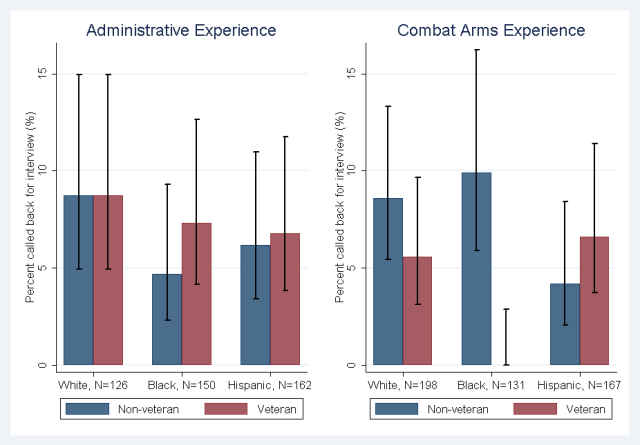

By conducting an audit study of hiring in a large city, I could control what my applicants presented in terms of skills and experience. In my first study, I paired male military and civilian applicants (on paper through resumes only), matching them on race, education, previous work experiences, high school quality, and current neighborhood characteristic. I had different “teams” or pairs of resumes for white, black and Hispanic applicants, and also had teams in which the military veteran had been in a human resources position in the Army, and another where the veteran had been a tanker in the Army. The first group provided a direct matching of functionally equivalent work experience (i.e. human resources), with one being done in the civilian market, and the other in the military context. Because there is no civilian comparison to working on tanks, I paired this resume with the same civilian resume with HR experience. In this sense, this second team differed in actual skills, but reflected the real experience a recent veteran of the combat arms would face—competitors for jobs who have typical civilian jobs.

All the jobs I tested were entry level, required no special skills or credentials, and all applicants had some experience with retail and food service work in their past work history. That is, all were designed to look like typical entry-level applicants with a bit of a checkered history of early low-skill jobs, but some degree of increasing responsibility in recent years. All had some college credits but no degree completed.

When it comes to a sharp test of discrimination of veterans with comparable, transferable skills that employers understand, the results are striking—veterans were treated the same or better than civilian applicants across all racial subgroups. As Figure 1 shows, for black applicants the advantage of being a veteran was substantial, with 7.3% of applicants generating a callback, versus 4.7% of black civilians. White veterans and civilians were on average treated the same, while Hispanic veterans held a very slight advantage relative to their civilian counterpart. While a callback isn’t a guarantee of a job, it is the point at which most candidates are excluded from consideration and past research suggests 75% of discrimination happens at this first cut. And these low call back rates show just how challenging it is to find a job by applying to positions publicly advertised.

Figure 1: Callback rates in audit study of veteran hiring, Kleykamp 2009

When comparing the same civilian resumes against a veteran without clearly transferable skills because they served in the combat arms, a different, more opaque story emerges. What stands out is black veteran applicants, who were advantaged when they had transferrable skills, now show striking disadvantages. Of the 131 applications sent out, not a single one for the black tank veteran garnered a response, whereas roughly 10% of the black civilian applicants did. Among the Hispanic applicants, the combat arms veteran was preferred. White veterans were also called back less frequently than their civilian peers. These experiments are designed to primarily offer descriptive causal evidence of differential treatment, but don’t offer many insights into why differences arise. For example, I have wondered if the preferences for Hispanic veterans with both transferrable and non-transferrable experience may relate more to military service serving as a mark of legal status than being about military experience alone. Just as statistically-discriminating employers may treat black applicants as if they had a criminal record, until evidence is presented to the contrary, employers may treat Hispanic applicants as possible illegal, without additional evidence of legal status. We can only speculate about why these results are so variable, but the treatment of black veterans seems to be highly influenced by their military occupational specialty.

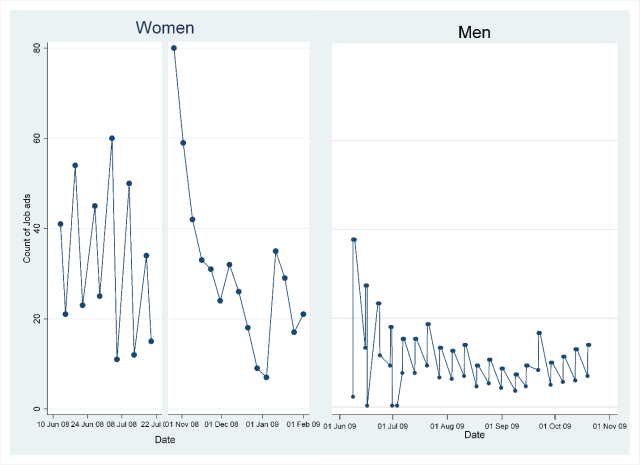

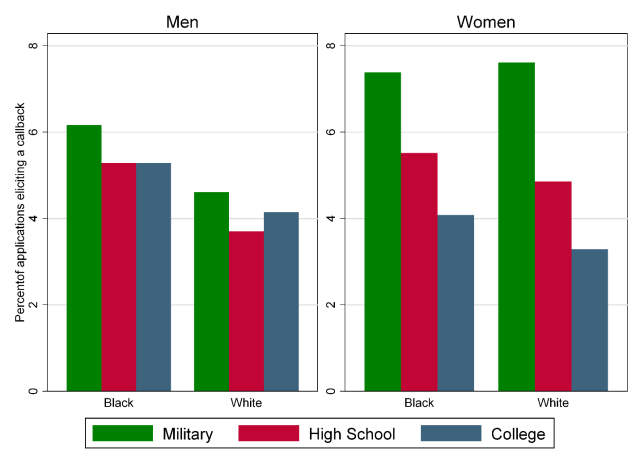

I conducted a similar study several years later in which I chose only to test military applicants with transferrable experience, again in HR. This decisions was largely the result of wanting to test treatment of male and female applicants, as women were not allowed to serve in combat occupations. This study was conducted in 2008-2009 as the recession was hitting and the veteran unemployment problem rose in prominence as a policy concern. In it, I matched a veteran with two civilians that differed in education, and I tested both men and women. Figure 2 gives some insight into just how the recession influenced the entry level labor market—our study went from an average of around 60 jobs for testing per week to about 10 advertised positions weekly over the study period.

Figure 2 Count of jobs identified for testing in 2008-2009, Kleykamp 2010 and unpublished results

The results from this experiment, using only the veteran with administrative experience, parallel the results from the first study. For men and women, black and white, the military veteran was equally or more likely to be called back for an interview. In this design, the veteran had only a high school diploma, and there were two civilian comparison testers—one with a high school diploma only, and one with a Bachelor’s degree from a local college. The veteran was called back most frequently, even over someone with a higher level of education. As with the first study, veterans serving in a transferable occupation showed a marked advantage over their civilian counterparts that held across race and gender.

Figure 3 Callback rates for audit study of veteran hiring, Kleykamp 2010 and unpublished results

Discrimination or Skills Gap?

There are plenty of critiques of these kinds of field experiments; if you’ve read Freakonomics you are familiar with one, regarding the correlation of race and class in names (which are used to convey race on paper). While a good experiment provides the experimenter with a great deal of internal validity, they tend to do so by sacrificing external validity, or generalizability. So the academic or researcher may be more likely to believe there is a causal relationship between the treatment and the outcome in experimental data, but to get that causal validity, we often have to create somewhat unrealistic or narrow circumstances for testing. In these designs, the findings only extend to entry-level jobs, advertised in the classifieds, in select geographic locations. The only treatment examines a veteran with administrative experience or tank experience, and doesn’t necessarily extend to those from other military occupational specialties.

Nevertheless, these findings altered my perspective on veterans’ employment challenges, and continue to shape how I think about the right kinds of policy approaches to solving those problems. Once something is labeled a problem for policy to address, it is of vital importance to understand the fundamental causes of the problem to get the solutions right. Much of the talk about veteran unemployment early on centered on discrimination, but my research has shown that there are other more significant challenges getting in the way of veterans success. If we don’t study or evaluate the problem, we may be designing solutions that don’t match the problem. These wrong-headed solutions may simply be ineffective and waste valuable resources. We assume that any policy meant to help will do that, or at least “do no harm.” But combined with a lack of policy evaluation of effectiveness, it may well be that we implement solutions that actually make the problem worse!

Over the past decade we have seen solutions to the problem of veteran unemployment in the form of increased transition assistance programs before separation to help soon-to-be veterans understand their job prospects and how the civilian labor market functions. There have been employer tax credits for hiring veterans, and initiatives to hire more veterans into the federal government, on top of existing veteran preference programs. There have been a proliferation of job fairs, and military-specific job boars and recruiting fairs. And veteran advocacy organizations like IAVA and Got Your 6 have produced public awareness campaigns meant to change employer mindsets about what skills veterans bring to the workplace, and to dispel myths about veterans. Most of my research over the past 5-10 years has intended to interrogate these policies or the assumptions on which these policies were crafted and implemented.

Based on my field experiments of hiring, I have come away rejecting the view that veterans are, on the whole, discriminated against in their job searches. Discrimination is differential treatment, on the basis of a social category, that disadvantages that categorical group. When we can isolate all other factors, it appears that veterans are either treated the same, or better than non-veterans, which fails to meet the definition. When veterans are treated worse than comparable civilians, it turns out they aren’t quite comparable—they have different work experiences (as we say in the tanker vs. human resources match-up). So the differential treatment can’t be said to only be based on the social category “veteran” per se, but rather could be based on different skills and experience resulting from military service. If the source of difference is a lack of relevant, transferrable skills or experience, we should be working to ensure veterans are trained or re-trained to have crucial skills to offer. Even in occupations with immediately applicable skills like pilots and medical professionals, the military should strive to align with the equivalent civilian certifications, giving these veterans a more seamless transition to the civilian workplace. When veterans have transferrable skills, they appear to be largely advantaged over civilians. But when we ask that veterans be treated differently, and to not be held to the same standards as civilians in education or the workplace, we may not be helping veterans succeed at all.